Charting a Course – Chapter 2: Guiding Principles for Water Governance and Management

Guiding principles are often cited or proposed in water policy and strategies. Principles exist at different levels, ranging from high-level aspirations to more pragmatic, management-level or action-based objectives. In this report, we consider guiding principles as a set of statements that either reflect the values of a jurisdiction or provide guidance on best practices for governing behaviour. Consequently, guiding principles are developed to ensure that an organization’s or jurisdiction’s values are respected, or that best practices are incorporated when making decisions and setting policy.

The NRTEE’s consultations and engagement for this report lead us to recommend that clear governing principles for water be articulated and applied. In this report we consider principles as a set of statements that provides guidance on best practices for governing behaviour and making decisions to achieve desired outcomes. Their absence will lead to uneven and fragmented water-governance approaches across our country. It will be harder to assess trade-offs and make choices on water use. Principles can rally and focus Canadians in our combined efforts to make this most critical resource sustainable for us all.

We propose a set of principles that sets the context for our research and findings, and frames our conclusions and advice. We put forward these principles to be considered in future water governance and management strategies across Canada, as they provide guiding conditions for setting down water policies in our country.

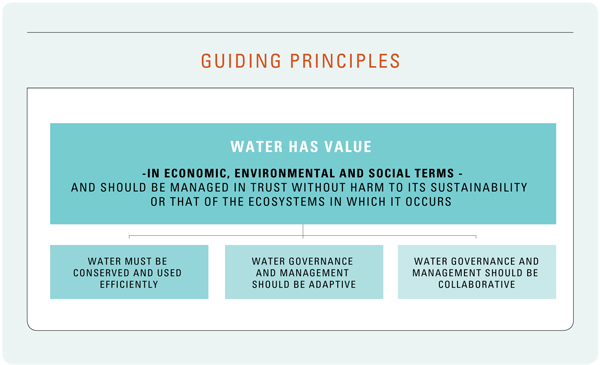

The NRTEE proposes one central principle to guide water governance in Canada, setting the stage under which three operational principles are proposed (Figure 1).*

FIGURE 1

CENTRAL PRINCIPLE

Water has value — in economic, environmental and social terms — and should be managed in trust without harm to its sustainability or that of the ecosystems in which it occurs.

The NRTEE’s central principle is multi-dimensional.

The first component recognizes that water has value in economic, environmental, and social terms. It is a critical input to all activities in the natural resource sectors, making development and production possible. Past failures to recognize the economic value of water has led to wasteful and environmentally damaging uses of our water by some industries. In recognizing that water use creates wealth, its core economic value can be revealed through a better understanding of costs and pricing. And with an understanding of this value, water will be better appreciated, more willingly conserved, and more efficiently used.

From an environmental perspective, water is vital to ecosystems, biodiversity, and human wellbeing. Watersheds provide critical goods and services such as keeping water clean, storing water, and providing habitats for fish and wildlife. There is a fundamental need to secure adequate minimum flows of water to maintain ecosystem services and functions, and to support basic human needs now and in the future.

Finally, water has a social value — an intrinsic non-market value that cannot be monetized but should be recognized and respected. Water policies should reflect the current social and cultural values of Canadians. Such values may differ regionally across Canada, which in turn may result in a variety of approaches to water governance and management.

The second component of our central principle recognizes that water should be managed in trust. Water is a public resource, requiring it to be managed for the benefit of both present and future generations and for the benefit of the natural environment. In managing our water, governments should take a preventative and precautionary approach, as prevention of harm is better than subsequent compensation or remediation.7

In addition, as water is a public resource, citizens have the right to know how it is used and managed. Therefore, there should be a presumption in favour of a public right to access data and information about water resources.

OPERATIONAL PRINCIPLES

With the context of the central principle, the NRTEE’s conclusions and advice is based on the following three operational principles that can be applied to the natural resource sectors:

- Water must be conserved and used efficiently

- Water governance and management should be adaptive

- Water governance and management should be collaborative

WATER MUST BE CONSERVED AND USED EFFICIENTLY.

In areas of water scarcity, water conservation and efficiency are cornerstones of any sustainable water policy and strategy. But even in areas where water is not currently seen as being in limited supply, conservation and efficiency remain critical for guiding future water policy and management. Without currently knowing what our water supplies and demands will look like into the future, the precautionary principle of sustainable development requires us to err on the side of caution and wisely use the water we have.

Water use by the natural resource sectors creates wealth and as such it should be used to its full potential. With its economic value recognized, and further established with pricing mechanisms that increase its cost of use, the value of water will be appreciated. As a result it will be willingly conserved and efficiently utilized. This will lead to both improved economic and environmental outcomes.

WATER GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT SHOULD BE ADAPTIVE.

Future water supply and demands are uncertain due to increasing pressures and climate variability. Our knowledge of current as well as future supplies and demands is limited, creating further uncertainty. Therefore we need to set up conditions that will allow us to deal with these uncertainties — conditions that will position current water-management systems to be adaptable, with a notable need to improve knowledge and information and consider additional tools to promote conservation and efficiency.

Adaptive management, the process of continually incorporating newly gained knowledge or information into decision making, can improve how we manage risk related to water uncertainty. Improved monitoring is a necessary component of adaptive management frameworks. It is important for water authorities to gather the right information and knowledge that will let them know whether actions taken to prevent or reduce negative impacts on the environment are working. Similarly, policy strategies, which include different types of policy instruments, may need to be updated allowing water managers the flexibility to react to changing circumstances and increasing knowledge bases.

WATER GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT SHOULD BE COLLABORATIVE.

While jurisdictions have both differentiated and shared responsibilities for water management, watersheds can cross jurisdictions, necessitating collaborative decision making. Three concepts are embedded within this principle: watersheds as the unit of management, a participatory approach, and stewardship.

Adopting a watershed approach to management helps to keep a core focus on the resource and its ecosystems. As such, a watershed defines the unit of water management by natural boundaries instead of geopolitical boundaries. This approach requires that jurisdictions work across political boundaries, which is a challenge given different federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal perspectives on water policy and management.

This principle also recognizes the importance of taking a participatory approach to water governance and management. A participatory approach involves engaging key interests and stakeholders in planning and decision making. It means that decisions about planning and implementing water projects are taken at the most appropriate level, with the inclusive involvement of water users and those affected by the water use. Such an approach supports the idea of greater transparency and accountability. Water governance and management needs ongoing accountability to key interests and the public.

Finally, this principle recognizes the concept of stewardship. Stewardship understands that people are part of the environment and that water users and managers have a duty to ensure their actions safeguard the resource and its surrounding environment. Stewardship requires the co-operation and coordinated effort of individuals, governments, boards, organizations, communities, industry, and others to be successful.8

APPLYING OUR PRINCIPLES

Defining these principles first is important, as we respect these principles and demonstrate their application through our advice and recommendations in this report. These principles are used as a frame and a filter through which we reviewed our findings and conclusions. We will show they can be put into practice through new policy research and future water-management and governance practices.

________________ Footnote

8 Government of Northwest Territories 2010

* These principles are based upon those found throughout water policy and management literature.